|

|

|

| Great Basin National Park | Hawaii Volcanoes National Park | Ellis Island National Monument |

The U.S. National Park Service (NPS) administers more than 400 sites, including national parks, monuments, battlefields and military parks, historic parks and sites, recreation areas, lakeshores and seashores, and other scenic areas. Each site is significant for its own reasons, whether because an important historic event occurred there, because of the presence of unusual geologic formations, or because of its unique ecosystem.

The NPS tracks data on its visitors in various ways, including through open-ended written surveys of how they understand the significance of the different park units. I was curious about how these data might be used to understand visitors’ experiences with the NPS and the similarities and differences in how they experience its different sites. To this end, I used a variety of natural language processing algorithms to analyze this year’s surveys (as of 10/31/2016). The data include responses from 40,380 unique park visitors covering 320 NPS sites. There were between 3 and 262 visitor responses per site.

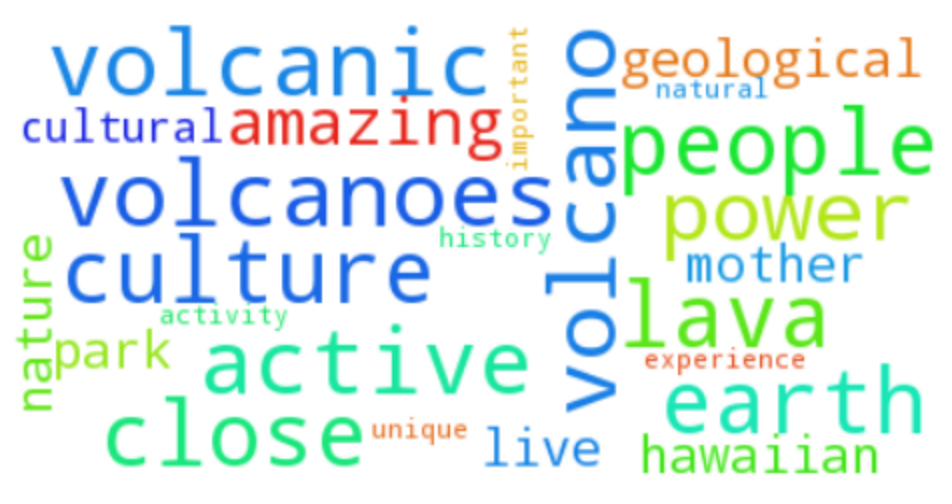

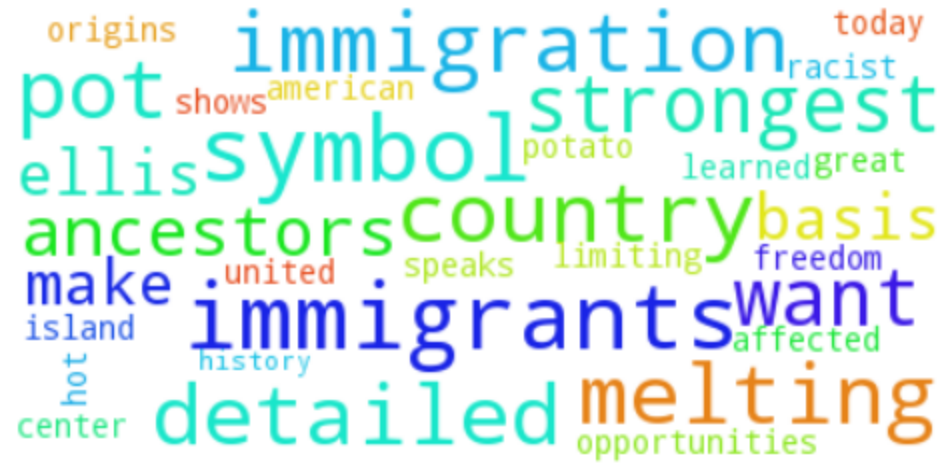

I analyzed these data in several ways. First, I conducted a sentiment analysis of the individual survey responses using TextBlob, and then averaged the results by park site to see which sites received the most positive descriptions. While several – including Great Sand Dunes National Park, Big South Fork National Recreation Area, and Abraham Lincoln Birthplace National Historic Site – did stand out above the rest, overall the main takeaway was that visitors’ descriptions of park significance are not especially emotionally laden. Second, I used TFIDF vectors to identify the most distinctive terms visitors used to describe each park site. The word clouds above highlight the top terms for several example sites.

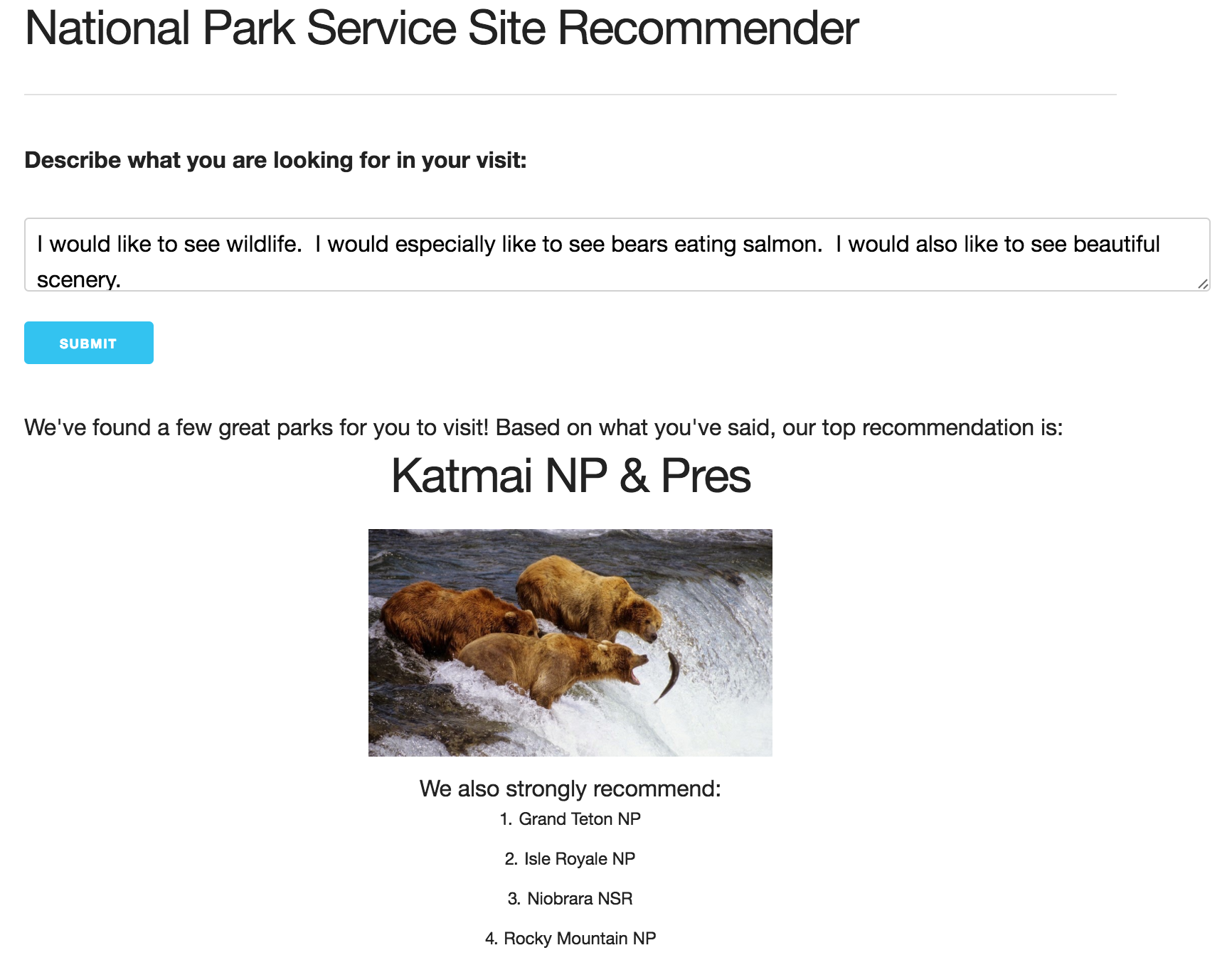

My favorite approach to the data led to a content-based recommendation system that takes input from a potential visitor and uses it to suggest the park sites s/he would be most likely to enjoy. To do this I began by merging all visitor responses from each park site into a single document. I then used a word2vec model trained on Google word vectors (available here) to generate a single 300-feature word vector for each NPS site. This same model is used to generate a comparable vector based on the potential visitor’s description of what s/he would like to see or experience during a visit to an NPS site. Finally, I use cosine similarity to compare the user input vector with the vectors from the NPS sites, and return the top five sites as suggested destinations. For example, consider a user who writes: “I would like to see a rainforest. I would also like to go for a hike on the coast or in the mountains.” The model’s top suggestion is Olympic National Park, WA. The next four are Great Basin National Park, North Cascades National Park, Congaree National Park, and Big Bend National Park. To demonstrate the system I also built a simple web app that uses a text box to accept the user input and shows the name and a photo for the top suggestion, followed by a list of the next best sites. This picture shows the output for a second example:

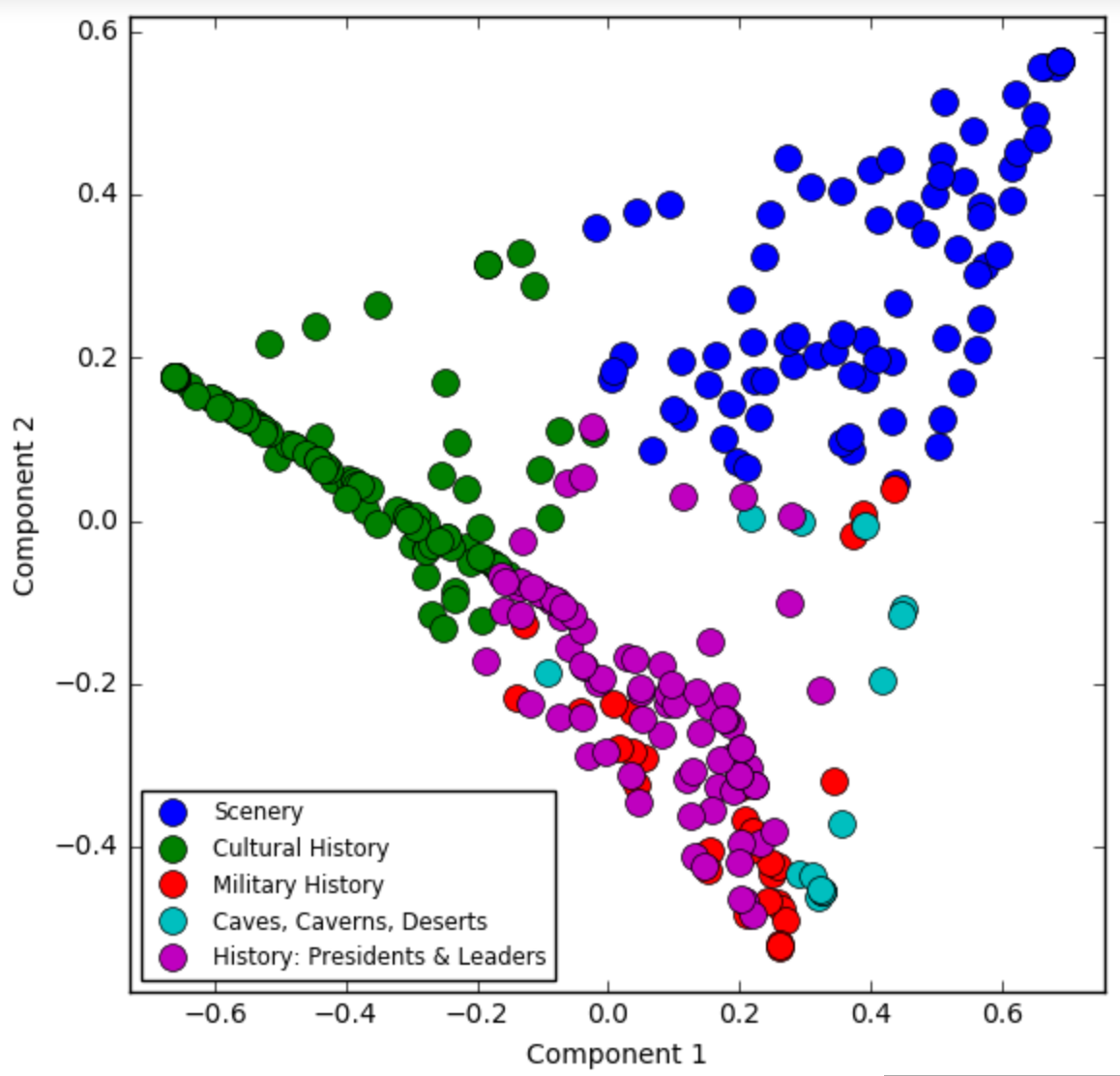

Finally, I performed topic modeling followed by clustering on these same merged documents. The NPS categorizes each park unit according to the types mentioned above: national parks, monuments, historic sites, etc. I wanted to see whether clustering the NPS sites based on topics highlighted in the visitor surveys would yield a similar breakdown of unit types or whether it would point toward an alternative way of thinking about the distinctions among them. For the topic modeling I used a hierarchical dirichlet process (HDP) since I didn’t know in advance how many topics I was looking for. It yielded 150. I then used the proportions of each topic in the different documents as features in a K-means clustering model. While there were several reasonable possibilities for the number of clusters, I ultimately selected five. The figure below displays these clusters in two-dimensional space after using principal component analysis (PCA) to extract the top two dimensions (which together accounted for about 48% of the variation in the clustering).

I was quite impressed with the results of this process. In eyeballing the park units within each cluster, I was able to identify clear and meaningful patterns that reflect some of the same distinctions the NPS uses to distinguish between different types of units, but that in some respects also make more sense from a visitor’s perspective. The labels in the graph correspond to the major themes that appeared to me to be central to each cluster. The dark blue cluster contains numerous national parks and monuments. While these are different types of NPS units, the unifying element is that the sites in this cluster are generally known for their scenery and natural features (whether forests, geology, biodiversity, or a mix). Similarly, the aqua-colored sites span multiple types of NPS units but are united mainly by a more specific type of natural feature: caves and caverns. The green cluster, too, includes several types of NPS units, but most of these sites have some affiliation with culture or cultural history. Finally, the red and purple clusters are again more specific. The red sites include national monuments, historic sites, battlefields, and military parks, but reflect a clear emphasis on military history. The purple sites are the least diverse in terms of NPS unit types: almost all are historic parks or sites. While they reflect many aspects of U.S. history, the most prominent theme appears to be presidents and leaders: around half of these sites are presidential birthplaces, homes, or similar locales.

These groupings make considerable sense. For a visitor who is interested in military history, the distinction between relevant historic sites, battlefields, and military parks may matter little. Instead, it is the military theme that is most salient. Similarly, a visitor who is seeking out natural beauty and outdoor activities may be equally satisfied by a visit to a national park, national monument, or national lakeshore. Organizing NPS sites according to topic-based clusters in this way might thus be another useful means of helping would-be visitors identify the sites likely to be of greatest personal interest.